- Campuses :

- Twin Cities

- Crookston

- Duluth

- Morris

- Rochester

- Other Locations

center for writing

mwp.umn.edu

Abigail Rombalski

©2013

Grandpa, Mandela, DeShawn, and Me: What’d You Learn in School Today?

Grandpa, Mandela, DeShawn, and Me: What’d You Learn in School Today?

The comb scrapes across Edward’s exposed scalp when Beulah beats him to the sweep and does it for him. Thinned greasy hair that doesn’t fill every tooth of the pocket comb. He sits at the table, waiting for the meal to be passed in clockwise fashion. In Edward’s mind, once he says grace, it is time to eat.

These kids are so dang noisy. Can’t a man eat a nice meal in peace? What about listening to me? I know it won’t be Doug or Diane; they are always too busy. Which of their kids would take a minute to listen? I swear no one would dare do this at my father’s table.

“Oh! The buns!” Edward’s wife, Beulah, jostles back to the kitchen, taking a minute to blot the corner of her mouth with a lipstick-stained kleenex from her apron’s left pocket.

Why can’t everyone just sit down. My daughter Diane keeps repeating, “Dad. Dad.” waiting for me to look up at yet another round-table picture, since some of the kids still make a face for the first shot. Good thing I can pretend to not hear her, and they shoot the picture from behind me instead. The freeze frame is perfect, everyone smiling and looking at the camera, the table set just so. There is still no food in my mouth and no one to listen to my stories.

----------------------

I’m the one with the hot pink side clip.

This is the view of the table from just near my Grandpa’s seat.

My grandpa sits on the far end of the dining room table, the head of the oval, with my grandma in a runner’s station in between the kitchen and dining room, a tv tray her table. In the photo, she’s in my mom’s seat. Grandpa yells a little, short clips, almost to himself but meant for us grandkids or our parents, about quieting down at the table or listening to him. We grandchildren pay his request, or his warning, little heed; our own parents are scarier. Plus, we are out of his reach. And even though Grandma told us her story about the time she had to join her sisters to pick her own switch from the trees in the back, neither of them had ever laid a hand on us.

Three generations around the table. We don’t understand each other nor the history of the table. The table I would describe as oval, thick and shiny hardwood that never peeks out from underneath three layers: raised mat, plastic, and a different pressed tablecloth for each season; my mother would label the table by brand: the Duncan Phyfe table that her parents had worked so hard to have: “When they were first married, they didn’t have silverware or indoor plumbing, you know.” It is interesting what being raised without much did for my mom’s brand awareness. Note that I’m not saying poor or struggling, because I never got that impression. Who needs indoor plumbing when there’s an outhouse; who needs indoor water when there’s a well and a pump outside. If you have what you need, and you work for what you have, you are never poor or struggling, you are just hard-working, no matter what you have.

----------------------

High school was walking distance to my grandparents’ house (and an hour-long bus ride home). If I ever swung by their house after school, my grandma would be in her beauty shop, the two rooms on the far right side of the house on Main Street, fixing ladies’ hair. My grandpa, retired from about three jobs now—farming and custodial work at the university and then at the bank—would sit me down with a bowl of cereal and ask what I’d learned in school that day. I really had to think to come up with something good, or something that I thought we could talk about, something separate from the social or athletic world that constructed so much of the day. Something that I actually felt I learned. The most I thought about the academic side of school was when I was doing homework, until Grandpa asked his question. Then I not only reflected on what I really learned, I also wondered if he asked because he never got to go to high school. I always thought I knew why.

Edward Albert Peter Bakken

Proof that if you don’t take the time

to learn the whole story,

or at least the whole of a small story,

you may never know the truth of any of it.

And then, really, where will you be

Will you think you are somewhere,

and the whole time

you will have been somewhere else

Like one story

that only surfaced his 96th year

talking after dinner and bingo

about the Indian band, Winnebago or Ho-Chunk, maybe.

Called the Coveralls, on account that they wore coveralls,

and whose ladies would go around to cars and steal all sorts of things

while the band played their songs.

Or the themed stories that kept hinting to re-surface

like when Grandma had to sneak her trash out with her sisters

when they came to play cards:

Don’t tell Edward.

When she mailed chocolate chip cookies to me in college

in a Pringle’s container

perfectly baked to fit

just so she could get it out of the house.

What did I learn in school today?

Maybe it’s the wrong question to ask.

I don’t want to forget

where I have so much I can learn.

But until I asked the right questions, the stories stayed the same.

And once I asked, and listened, everything changed.

How long does it take to learn to listen?

My grandfather’s formal education led him through 8th grade, through a test that asked math questions about measurements in bushels and rods. He walked or sometimes got a buggy ride to the one-room schoolhouse, where he had to sit in the first row in between two girls to keep him in line. Everything beyond that was gleaned from the world around him, both in print sources and real life experiences. The La Crosse Tribune with its front page, funnies, and obits, the Onalaska Herald with the local spread, the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse employee paper and their ads. For his grandchildren, we who wouldn’t listen at the dining room table, he kept a mental running record of anything related to us in his world: Once my cousin Shelley and I became secondary school teachers and coaches, he told us each time there was an opening at the university, the sale of an old school desk, and the sports scores from the nightly news. He saved every scrap of paper or mind puzzle that we might use with our students. He watched the world weather map on the back of his newspaper when I lived in India and when Shelley visited South Africa. He counted Sysco trucks as they passed by his picture window and saved advertisements from Rubbermaid, Bose, and Best Buy, all reminders of his grandchildren’s places of employment, whose companies passed through his house more than we did ourselves.

Still with an insatiable appetite for news and for sharing, the small print doesn’t work with Grandpa’s glaucoma anymore. He won’t use a magnifying glass, probably because he doesn’t have one, doesn’t have a way to get one, and would never ask for anything. So instead, he relies on a little old man gossip with his brother’s daily calls, large print Reader’s Digest and church bulletins, and anyone else who will call or come, sit, and spend some time.

Grandma and Grandpa sent me letters through college, as well as on my birthday until I was probably 30 and Grandpa Ed 90. Since I’m a teacher, when they wrote, Grandpa would add, “I hope I get a A” on his letters. I’d call, and he’d ask me, “What did you teach those kids today? Did they pay attention and learn something real good?” It sure made me think, just like it had in high school. What was I teaching my kids? Were they paying attention? Was I teaching them something, anything, real good, every day?

Unless we ask,

unless they tell us,

and unless we listen

It takes so long to learn.

----------------------

What did you learn in school today? I know it wasn’t how to talk to girls like what your mom showed me you wrote on that computer FaceBook. Don't let your ears witness what your eyes didn't see & don't let your mouth speak what your heart doesn't feel.

DeShawn’s grandmom, mom, and his sisters took him to town, read him an act, and whooped his metaphorical behind. Downward fell his eyes, his head, his chin, dropping with the tiniest bit of reverb, like his head was on a marionette string connected to a falling kettle ball. Within minutes, his next post was an apology to all women: his mom, his grandmom, his sisters, and “all the other women in my life and in the world who deserve my respect.” That apology post? LMS by 45 and climbing, many more than his initial trifling teenage comment.

Anymore, who knows what was said, but it was something in between:

You want us to be Superman but you aint no damn Wonderwoman

and

B**, if i slap you with my left hand even though im right handed, did you still get slapped?

The lesson was learned and the flow might be cheesy,

but respect will win you more females than greasy.

You see them other guys pay they mind to your physical features/And I can admire your body, but your mind is much deeper/I found me a keeper/I found me a winner/I found me a queen.

DeShawn (renamed), pictured here a few years after he was in my 8th grade class

So really, DeShawn, what’d you learn in school today? There had to be something else. Some Christopher Columbus or Angela Davis? Don’t make me take my dusty brain off the shelf.

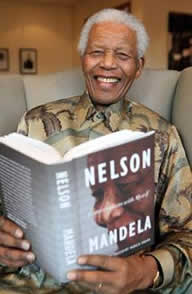

Okay, Grandmom, okay. We’ve been learning about Nelson Mandela. He’s this Black man who was in prison for almost 30 years. He’s almost as old as Ms. Rombalski’s grandfather, just a few years younger and almost 9,000 miles away. He grew up in a tiny village, without running water, went to a one-room school house until he has 16 and then went to college. He organized and fought against the segregation, the apartheid, in South Africa, and got sent to prison. And after that, you know what, Grandmom? He became president of his country in a place run by white men before him.

When DeShawn first learned of Mandela, he chimed with his classmates:

He must have been in jail for something bad.

Did he rob someone?

Kill someone?

Carry drugs?

What did he do?

The perception of reality in the 21st Century

is that a Black man in prison must be there for a reason

must be overt; couldn’t just be treason

Students only don’t know

because they haven’t been taught

the possibilities

of political prisoners

non-violent protestors

pastors and preachers and moms and dads

defiance of rights denied

standing up for others

sitting-in solidarity

Boarding the bus and banning the bus

Food strikes and hunger strikes

So Ernie Banks could win the right to strike out

And Charles Hamilton had right to strike a motion

From Romana Bañuelos to Rosa Rios caring for the US debt

and Madam CJ Walker making a million with science and scalp lotion

So DeShawn wondered,

as his world now taught him he could,

how this Black South African was in prison

for good

And then his friends,

not knowing what to believe

about Huey P. Newton, Rosa Parks, Malcolm X, MLK,

They must have been in jail for a reason

It couldn’t have been just a cause they believed in

Not knowing what to believe about fathers, uncles, brothers either

Was their run-in with the wrong type of Cesar

They marveled at Mandela

and then they wondered deeper.

Nelson Mandela, reading his own book, Conversations with Myself, in large print.

They wondered

About his time, his words,

what he taught and what he learned

How lessons travel from Delhi to Delano, Cape Town to Montgomery to Minneapolis

They wondered what justice will mean in their turn.

---------------------

What’d you learn in school today? Today my Grandpa got to ask my students that question directly. They were Skyping with him from my mom’s iPad in Wisconsin to the school’s media center in downtown Minneapolis. They had been reading a story set during the Great Depression, and they had questions prepared to ask him. I told them earlier that Grandpa Ed only went through 8th grade, that he had to stay and work on the farm in the 1930s. A student of mine asked him why. Finally, I listened.

All the banks were closing, were losing their money. There was a run on the banks. The value on all the farmland went down, so taxes went down and there wasn’t money to pay the school teachers. I could have gone to school, but I would have had to board, that means to live in someone else’s home and pay them rent. The closest school was 16 miles away from home. There was no way to get there, and no money to board. Plus, they could use me at home on the farm. Schools shut down all over. (When I fact checked later, I learned that the Great Depression left 3 million students in the U.S. with no school.) That’s why you have to learn all you can while you’re in school. I don’t write so good, but you can. You have a good teacher there. Listen to her.

Ever since I was in middle school, I knew that Grandpa only went to school through 8th grade, at the one-room schoolhouse on the ridge. I even visited the land and took a goofy photo poking my head around the wooden, brick-colored outhouse with its crescent moon window at the top. I knew that he always saved everything, like the Folger’s coffee tin full of pencil nubs and another one full of nails removed from projects at work or around the house. But I’m embarrassed at all the times that I sat around the table with him, that I never really knew why he stopped going to school, until now.

Unless we ask,

unless they tell,

unless we listen.

What’d you learn in school today?

Today, I learned to listen.

Hopefully tomorrow I’ll learn to question,

so that I can listen and learn all over again.

Love you, Grandpa. I’ll call you tomorrow.

I’ll try to learn a lot in school today, I promise.

Grandpa Ed and me at my wedding in 2006.